Embracing the Rhythms: Ethiopian Dance in Focus

To ensure cultural accuracy, the artists were given their choice of a selection of photographs to use as inspiration for their pieces. Below is more information on the dance or images being depicted, as well as photo credits. Jane Kurtz, author of the Ethiopian Dance book, wrote the background information.

Ethiopia’s most southern ethnic group is the Dassanech. They live in southern Ethiopia and northern Kenya in the delta of the Omo River and north of Lake Turkana and are the largest Omo Valley community that has retained its traditional lifestyle, culture and villages. Recently, pumps from the Omo River have brought new farming opportunities to the hot, dry land where the Dassanech have long tended herds of goats and cattle. An important dance ceremony for the Dassanech is called Dimi, a time when fathers celebrate and bless their daughters for marriage. Australian photographer Jayne Mclean, who has many images of women and girls on her site, says that although “the ceremony is for the first born daughter the blessings pass on to any of the girl’s sisters whether they are younger or unborn.”

When a man has gone through Dimi, he becomes an elder and can take part in important decisions. Each morning, the parents and relatives of the girl being celebrated chant and dance to the rhythm of wooden instruments and bells strapped to their legs. They bless the homes of each of the girls.

Piper Mackay is another photographer who admires the vibrant culture of the Dassanech in both Ethiopia and Kenya. This painting was inspired by one of her photos and used by permission of someone who describes herself as “passionately creating images across Africa that touch the soul.

Wolayta was an ancient kingdom that was absorbed into Ethiopia in 1896. Its fast-paced tunes and lively, unique dances are well known throughout the country. Wolayta people play long flutes made from bamboo or sorghum stalks, buzzing their lips against the opening to create the pitch as with trumpets, trombones, and tubas. Music is used for entertainment, ceremonies, and religious occasions.

Wolayta songs are about paddling with the current, paddling against the current, politics, harvesting and other work, war, beer drinking, birth, admonishment, and humor, among other things. Group dancing–with lots of waist movement and athletic leaping–provides a chance for the community to come together, for people to mend bridges and find reconciliation within the community. The photo that inspired this painting was taken at a dance featuring different traditional dances in the Fendika Cultural Center in Addis Ababa.

Dancing in Ethiopia is often very athletic and might include stamping, shaking, leaps or spins. The rhythm is usually laid down by singing and clapping–and sometimes by various kinds of drums. Ceremonial drums play a part in Ethiopian Orthodox religious ceremonies and festivals and are also part of many weddings, funerals, and other occasions.

On feast days, the regular church liturgy is followed by singing, accompanied by drums and a stately kind of dancing. These traditions began in the sixth century when Saint Yared wrote music and incorporated drums and the begena, a 10-string lute, for spiritual ceremonies and for meditation and prayer. Melaku Belay from Fendika Cultural Center says, “This was our way to connect to God, and became the foundation of our musical traditions.” Today, drums show up in many places and on many occasions including Nations and Nationalities Day, a time to celebrate Ethiopia's more than 80 nationalities and ethnic groups.

The Gurage people of Ethiopia, according to the writer Nega Mezlekia, have long had a well-deserved reputation as skilled traders.The most well-known Guarge Ethiopian musician, Mohamoud Ahmed, started out in life working hard–first shining shoes in Addis Ababa and then doing maintenance at a music club.

When he got a chance to perform in the 1970s, he gradually gained more and more popularity until–over the decades–he became a legend, with millions of admirers both in Ethiopia and in other countries. In the Gurage home region in southern Ethiopia, music is an integral part of life, according to Melaku Belay, who often brings Gurage dancers to Fendika Cultural Center in Addis Ababa. Their dance features acrobatic full-body moves. The dancing is fast-paced–with hip shaking and leaps. The dancers have to coordinate their entire bodies as they move their arms and legs forward and backward. The photo that inspired this painting was taken at one such occasion in the Fendika Cultural Center.

Jess Markt, adviser to the International Committee of the Red Cross says, “It's incredibly common in developing countries — and particularly countries dealing with conflict — that people with disabilities tend to be the ones most forgotten, the ones the most marginalized.”

Addisu Demissie, company manager of the Addis Ababa-based dance group Destino Dance notes that typically in Ethiopia,“If someone had a person with disabilities at home, they wouldn’t allow them to go outside and meet the community or even to go to school.” With regular dance performances, the group is trying to show people what is possible. As one of the dancers puts it, dance changes things because it’s visible, and people believe what they see.

This painting was inspired by a photo provided by Addis Guzo Dance Group Ethiopia, a contemporary dance group aiming to empower people with disabilities.

The photo that inspired this painting was taken by Piper Mackay who travels often to Ethiopia to create compelling imagery and stories that make a difference, including to the Omo River Valley. The Omo River begins in the Ethiopian highlands and falls almost 2,300 feet as it makes its way down the valley. Its floods support life for hundreds of thousands of Ethiopians.

Communities that live some 350 miles south of the capital city of Addis Ababa are very different from those on the high northern plateau. They dress differently, adorn their bodies differently–often mixing water and minerals for colorful paint–and speak languages of the Omotic family (as opposed to the Ethio-Semitic languages of much of the rest of Ethiopia). Their dances are also distinct. Addisu Demissie, co-founder and manager of Destino Dance Company, says, “All in all when we look at Ethiopian traditional dance, it looks like the human body structure. From north by the way of the middle to south regions, the body movement goes down from head to toe. North focuses on neck and shoulder which continues to belly, hips and ends with foot movement.”

Across the Omo Valley, many communities live near each other but speak different languages (or dialects) and have different customs. Hamer women wear beautiful colorful beaded skins and metal bangles around their wrists and ankles. Ornate necklaces communicate status and are never removed. Their hairstyles are created from long dread-lock braids covered in a natural clay earth pigment.

Hamer men often spend days of work on their hair, sometimes adding natural, yellow or red color or feathers. The men sleep using a wooden cushion as a kind of pillow to keep the hairdo attractive. Across Ethiopia and beyond, the Hamer people are known for a bull jumping ceremony, a rite of passage for young men, a special event that requires courage, skill, and athleticism. On the day of the ceremony, between 100 and 300 people gather. Women jump and dance in traditional dress with bells on their legs. They sing and play loud horns. After the ceremony, a big dance celebration–when the young men who’ve successfully jumped the bulls have a chance to meet a potential wife–lasts most of the night.

Cave paintings more than 10,000 years old reveal that probably even the earliest peoples danced–and old etchings and paintings from around the world suggest that a circle is the oldest form of community dance. For thousands of years on many continents, circle dances have been a way to celebrate stages of human life, work, love and loss. They are choreographed to many different styles of music and rhythms.

For the many communities who live in Ethiopia’s Omo Valley, singing and dancing play a more important role than do musical instruments. Drums are not very common there, although some of the communities use drums during mourning ceremonies to announce the death of a person from a long way off. Instead of a sign of joy, the drums are a sign of loss. More common are five-stringed instruments made from wood or tortoise shell, horns, flutes or finger pianos. No matter how the music is made, circle dancing in the Omo Valley marks special occasions and rituals while it also strengthens community and encourages togetherness.

This painting was inspired by a photo taken by Piper Mackay, who often visits the Omo Valley to create compelling imagery and stories that make a difference.

Various stringed instruments, including ancestors of the American banjo, are part of dances across the African continent. Many Ethiopian dances incorporate the krar (five-or-six stringed) and masinqo (single stringed). Across the border in the Kenyan Rift Valley, Kisii songs and dances are accompanied by the instrument seen in this painting, called an obokano. In modern-day Kenya, dances are often prepared for tourists–as a way to preserve culture and teach about the old traditions–and are also still part of special village occasions such as funerals.

As one researcher puts it, “Songs and dances are ambassadors of Kenyan traditions.” That is true in Ethiopia as well. Melaku Belay from Fendika Cultural Center in Addis Ababa, who offers opportunities for visitors to see Ethiopian dances, has also toured throughout Africa and says that when we visit other countries, “we give who we are. We learn who they are.” A Sudanese visitor to Fendika says that he walked away thinking, “Who on earth created these borders between us?”

This painting was inspired by a photo taken in Kenya by an American woman with an Ethiopian husband and daughter.

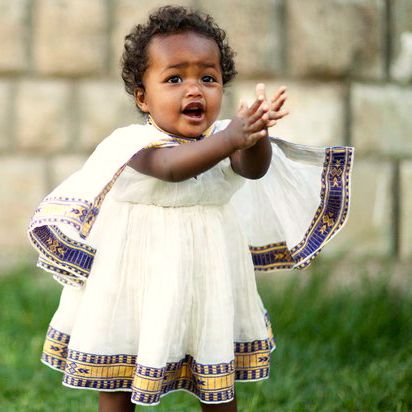

Ethiopian history dates back to over 3000 years, and Ethiopia’s folk dances reflect histories and customs from many ethnic/language groups–more than 80 dance traditions from all corners of the country, including those of the Amhara people, depicted in this painting by Ethiopian artist Eyayu Genet. Dance and music are still an integrated part of life for many Ethiopians.

Dancing has long been used to celebrate festivals, weddings, and occasions of every kind. It is usually accompanied by traditional instruments such as the krar, flute, drums and masinqo. One researcher writes that in the western world, we think of music and dance as two separate things but for Ethiopians, they are the same thing. Traditional dances and songs have the people’s own unique rhythm.” These days, many Ethiopians are calling for an effort to study and preserve traditional dance.

Meron Tsegaye, who teaches traditional dance, says that each ethnic group’s dances “should be studied, and classified into what is reserved for weddings, or funerals or festivals. We’ve not come as far as we should have with dance.” The work of organizations such as Fendika Cultural Center and books like this one will help.

In Ethiopia, traditional dances are used in the religious ceremony of Timket, or Epiphany. Fendika Culture Center founder, Melaku Belay, says, “To me, dancing is a kind of prayer.” When he was growing up in Addis Ababa, Timket–an important Orthodox church festival–was a time when the church came out to the people. The streets turned into a “huge melting pot of Amhara, Oromo, Gurage, Tigray, and Minjar music and dance. So colorful and powerful! That was where I learned how to dance.” Melaku adds that in those days, he didn’t see Gamo people from the south.

Now, they live in a neighborhood of Addis where they weave beautiful fabric and gather eucalyptus branches to sell. Melaku fell in love with their music. He often joins their dancing at Timket and says, “I love seeing men and women of all ages dancing together, people who are perfect strangers dancing the same rhythms, and giving each other hearty hugs afterwards. Even though they don’t understand each other’s language, they can communicate through body language. This is why I love Timket!”

This painting is based on a photo of Gamo dancers from the Fendika Cultural Center collection.

In 2013, Oregon photographer Joni Kabana was on an assignment with Mercy Corps, an NGO with headquarters in Portland that describes itself as a global team of humanitarians working together “to create a world where everyone can prosper.” She was asked to document a project with camel milk producers in Somali, a regional state in eastern Ethiopia, where she met Fatumo, a woman who spends her days milking camels near the Somalian border.

Joni writes about her experience on her blog: “We spend the day together, and she shows me what she does all day long, every day. We visit the other milk producers and initiate song and dance among them, pounding beats on the makeshift plastic milk containers as our drums, me singing the Somalian words that I did not know that I knew.” She adds, “Such joy, such camaraderie. I learn so much from them.”

One of Joni’s photos, used with permission, was the inspiration for this painting. Somali women typically dance with their hair covered with scarves, spreading their long skirts like the wings of butterflies.

Eskista is one of the best-known Ethiopian dances, especially in the northern part of the country, particularly in the state of Amhara, where it is performed by men, women, and children. It's known for its unique emphasis on intense shoulder movement and is performed with head, neck, chest and shoulders shaking in specific ways.

Melaku Belay, who founded the Fendika Cultural Center in Addis Ababa has earned the nicknames “walking earthquake” and “King of Eskista.” He says, “Eskista is deeply embedded in our way of life. Even though it's an ancient dance form, it can still tell contemporary stories of today.” According to folklore, he adds, it was inspired originally by a young woman “who hypnotized a snake by mimicking its own movements and sounds.” This painting was inspired by a photo taken at Fendika, which often features eskista from the ancient capital of Gondar in northern Ethiopia.

Ethiopian traditional dances are assumed to have originated during the Axumite period in the 4th century, when the Axum Kingdom was a major empire in Northeast Africa with tall obelisks, its own written language, and minted coins in gold, silver, and bronze that were used for trade with Rome, Egypt, Persia, and India.

Then, as now, dances would have been used to celebrate specific occasions and also served religious purposes; Axum introduced the Christian religion to the rest of sub-Saharan Africa in the fourth century CE. Through the centuries, these dances continued to be developed, incorporating storytelling and a variety of rhythms. In modern Ethiopia, Axum is part of the northern region of Tigray, where the shim shim dance is similar to eskista but slower. In the early 12th century, power moved south to the Amhara region, with kings ruling from places like Lalibela, Gondar, and Addis Ababa. Now every August, women in both Tigray and Amhara dance together during Ashenda, a colorful festival which celebrates women and girls.

This painting that shows those dancers is based on photos from the Fendika Cultural Center in Addis Ababa.

This painting was inspired by a photo taken by Yonas Tiku, an Addis based tour operator, while traveling to South Omo Valley. In Ethiopia, music for dancing on the northern high plateau is often played on instruments such as drums, the masenqo (a kind of bowed lute with just one string), and lyres with various numbers of strings. But as one development organization puts it, “how music is made in Ethiopia varies a lot depending on where you are and who you’re with.”

In the Omo Valley, some people play single-tonal bamboo flutes for dancing. Other communities make music with rattles. As Australian photographer Jayne Mclean writes, “There is nowhere else in the world with such a diverse and unique group of tribes living so close to each other than Ethiopia’s Omo Valley in the south west of the country.” People use a lot of beaded jewelry. Some of it is especially made for celebrations, including foot rattles and bells–or straps for the upper part of the arm that swing up and down during dancing.While northern groups in Ethiopia mostly use the upper body when dancing, dances in the Omo Valley involve jumps and footwork.

In Ethiopian villages and small towns, dancing usually starts from a young age and is passed on from generation to generation. Each dance reflects the group’s identity and includes steps and music unique to that group. Today, many Ethiopian traditional dances are also seen in places like the Fendika Cultural Center in Addis Ababa, shared in concerts outside of the country, and incorporated into modern dance styles.

With social media sharing dance performances, younger Ethiopians in the city are becoming more aware of the art form and are encouraged to try traditional dancing for themselves. As one researcher of East African dance says, “In the younger community dance is a way to gather, spend time together, exchange and grow, and to show yourself.” Meron Tsegaye, a dancer for the past 20 years, began to teach traditional dance about five years ago, and she reports that she has seen more and more urban young people interested in learning more and trying out traditional dances for themselves.

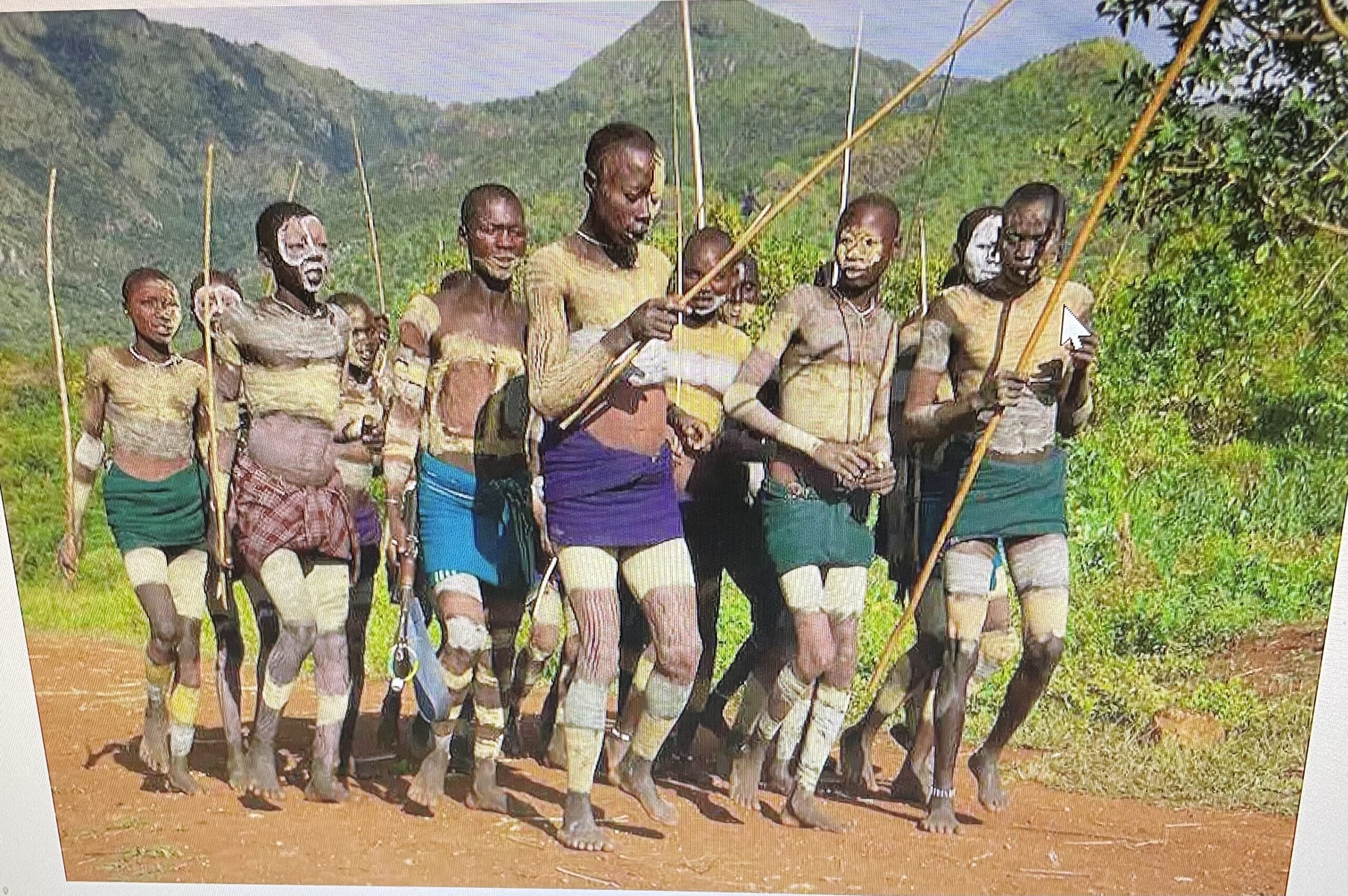

In Ethiopia’s Omo Valley, many different communities are living in close proximity, but as one writer notes, “clothes, body paint, hairstyles, piercings and scarification marks vary.” The Kara people paint their bodies and faces daily to prepare for their dances and ceremonies. They crush white chalk, yellow mineral rock, red iron ore, and black charcoal, often mimicking the spotted guinea fowl. The Suri community is in the remote West zone of the Omo Valley of Ethiopia, close to the border of South Sudan.

They live close to nature and often decorate their bodies with white clay in intricate patterns as skin protection, as part of ancient rituals, and as a way to express creativity. The Suri people love to sing and dance and they create massive contests tied to certain moments and activities in the cycle of Suri life.

This painting was inspired by a photo taken by Piper Mackay who travels often to Ethiopia to create compelling imagery and stories that make a difference.

The Gamo people are found in the highlands of southern Ethiopia. Gamo traditional dance forms have recently been adopted by musicians and seen in Ethiopian music videos, which has helped them to be more visible in their own country. A researcher of East African dance writes that local people who are interested in dance “can reach more easily to American or international influences than to their local articulations. It is harder for them to connect to the vast knowledge of their own culture, because this culture is hidden in the villages, and not vastly represented on the internet. Having access to actual village dancers is a great resource.”

Melaku Belay agrees. He says that many Ethiopians are ignorant about the diverse cultures in the South because they are not represented in mainstream forums. Singing, he notes, is a big part of Gamo culture and upbringing. “When I invited the Gamo people to Fendika 12 years ago, I fell in love with their music! And I continue to learn from them.”

This painting was inspired by a photo from the Fendika Cultural Center collection.

This mandala illustrates a collection of instruments in the Open Hearts Big Dreams Art exhibition that musicians might have playing for the dancers.

The Krar resembles a small lyre or harp. The curved-shaped body is made of wood or animal hide. The top bar has six or eight strings stretched across it which are typically made from animal gut or nylon. The musicians pluck the strings with their fingers or pick. Its’ distinctive sound is recognized by sharp resounding notes in a wide range of tones and rhythms.

The Masinqo is a traditional Ethiopian single-stringed bowed instrument. It is made of wood with a long, curved neck with a resonating chamber and horsehair string that is stretched across the length of the instrument. It is played by using a horsehair bow and the musicians fingers pressing the string onto the neck of the instrument to change the pitch and create a melody.

The Washint is a flute made of bamboo or cane that is custom made for each musician. Due to the placement of the finger holes each instrument reveals a different sound which is individual to each performer. Washint players perform with several flutes giving them flexibility to be compatible to the pitch of each song.

The Kebero or drum is made from a hollowed out tree trunk with hard particles placed within. The top and bottom are stretched with cow leather. One end can be tuned higher than the other. The drumheads are tied with lacings of twisted hide. The musicians usually play on the larger of the two drumheads and hang the drum on a strap over their shoulder.